Okay, okay, I do. I do believe in picking up trash. But I want to talk about why I am, by and large, opposed to trash pickups when it comes to youth development programming, and how I believe they can be done better.

I’ve organized a LOT of trash pickups. Working in community development in New Orleans, we were often besieged by volunteer groups looking for a project in a poor neighborhood. Often it’s more work than it’s worth to coordinate volunteer projects for large groups, particularly out-of-towners, so setting them to clear up trash from a few empty lots was an easy enough task that would keep them out of our hair.

I managed to stumble onto my first trash pickup in Morocco after only a few weeks in my site. For a combined Earth Day/Global Youth Service Day program, my counterparts and I organized a trash cleanup session for elementary and middle school aged youth.

Here’s how I wrote about it for Peace Corps:

As one of the events for our Earth Day/Global Youth Day of Service, the leadership of the youth center and the boarding houses organized a trash pickup in the area next to the middle school and the boarding houses. About sixty children came out and picked up trash, resulting in several large trash bags. That afternoon, there was a Powerpoint lecture at the Dar Chebab led by a teacher from the middle school. Everyone had a good time and the Moroccan counterparts felt the event was a great success.

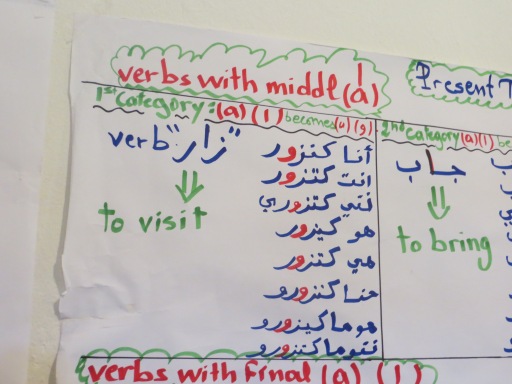

And I would have included pictures like this one:

Here’s how I DIDN’T write about it for Peace Corps:

The event was attended by a random assortment of students who were either yanked out of their classes by adults, or happened to have a free period at the time. The trash pickup was hugely ineffectual as we were picking up litter in an area strewn with trash, and it would have taken a monumental movement to make even a small dent in the aesthetic appearance of the site, let alone create an environmental difference. All this was conducted next to a HUGE trash pit filled with trash. Children were not provided with gloves, and much of the trash was unsanitary-looking – and, of course, there is no soap available for washing hands in the schools, the boarding houses, or in their homes. The large trash bags that were quickly filled were left on the site after everyone posed with them for several group pictures. It is unknown to me how they were eventually disposed of, but they were not there a few days later. (Hopefully they were not just rolled into the pit.) The lecture that followed that afternoon was about smoking and completely unrelated to anything resembling environmentalism or trash habits. Everyone had a good time and the Moroccan counterparts felt the event was a great success.

Clearly, there was way more trash than we were equipped to pick up.

Remember the giant trash pit?

I think, for youth and community development practitioners, organizing trash pickups is lazy. It’s a cop-out. It’s easily organized (if you’re not doing it right, that is), it requires minimal planning or materials, the idea is sexy, the photos are brochure-ready, the numbers shine on a grant. And for western eyes with a western conception of garbage and litter, an area with trash is so demonstrably aesthetically improved once the trash is removed that it’s easy to say: well, even if it wasn’t sustainable, at least it will be a little better for a little bit of time.

And remember, I say all this as someone who has organized way more than my fair share of trash pickups. No one needs to hear this message more than I do.

Here are Leah’s recommendations for how trash pickups should be done:

1. They must be sustainable. Are there going to be places that youth and community members can deposit their trash from now on, instead of continuing to toss it on the ground? Who will empty the newly installed trash cans? Where should they be installed? Where will the trash deposited into them (hopefully) be brought?

2. They must be accompanied by education. Community members will not alter their trash habits without significant education about why it is beneficial or preferable for them to do so.

3. The trash pickup must happen in an area where an actual impact can be made, and maintained – perhaps an area where youth are responsible for most of the trash, and not a vast pit where mothers put their trash because they have nowhere else to put it.

4. They must be done in an organized manner. Think team captains, quadrants, etc.

5. They must be done safely – with gloves, washing stations with soap, and so on.

6. The trash collected must be well disposed of, and this should also be a learning experience. Where trash goes and where this particular trash will go should be an integral part of the educational element.

7. They must teach work ethic. No picking up trash for 20 minutes, and then 10 minutes spent taking pictures.

8. The space where the trash has been picked must be USED afterwards. Is it just going to remain unused space? Then why bother? Consider sports area, park, activity space, etc.

9. Alternatively, the space picked should be a place where trash is actively creating a health or environmental crisis, and education can be used to show how the trash pickup is creating a positive effect on the ecosystem. Is it demonstrated that this trash is affecting a water supply? Is it demonstrated that animals are eating this trash and dying?

10. And, as with every single goddamn thing we as development practitioners do, it MUST be resident driven.

I struggle with all this a lot, but I’ve learned a little about trash in my time spent living abroad, and about my own conception of it. I had the hardest time in India, where the trash situation is even worse than it is in Morocco. If I was standing in the road outside my school building in India and eating a candy bar, I would save the wrapper until I got back inside and could deposit it into a trash bin. And then I would watch that trash bin get emptied out onto the curb right where I had just been standing. I really should have just let that candy bar wrapper drop right where I had eaten it. I would have been saving myself time and energy perpetuating my Western conditioning, which was completely untenable in that environment.

That conditioning was so strong, however, that I just couldn’t bring myself to so blatantly litter – and so I continued to let Indians do it for me. Looking back, I feel my behavior was fairly disgusting. There I was, insistent on carrying out a fairly meaningless ritual just to make myself feel better, and letting Indians (who were employed by my school, and therefore working for me) do the literal dirty work while I sat on my righteous American pedestal as a non-litterer. Oh, pat me on the back and give me a banana. (I’ll admit that by month four I had gotten over this and was able to litter, a little, though I could never get over the guilt of letting something just drop from my fingers into the street.)

Some of my classmates in India felt that the Indian relationship to trash was actually more honest. Whereas Americans had found a way to sanitize the experience of trash, to hide the reality of our consumptive and materialistic natures away in covered landfills (where only poor people would have to see it), Indians were confronted by their trash every day. They were living with it. Who’s to say which approach was better?

Well, I’m not ready to go that far yet, but I am comfortable saying that conceptions of trash radically differ in the world.

Working with youth in Morocco, the best way I’ve found to connect littering to hurting the environment is to connect it to nationalism and national identity. You know, when you trash you are hurting your country/your mother land, don’t you love your country, why are you hurting it, etc. It’s effective for getting a group of youth rallied up and (hopefully) receptive to your message, but I’m uneasy about the implications of using nationalistic rhetoric in this way. Ideally, one would cultivate the idea of “environmentalism” first and then discuss trash. And if you’re working with youth and you are able to invest the time and resources to communicate – and, ideally, instill – environmentalism, then might there not be better things to rally around? Clean water access, say? Less pollution? Green alternatives? Might trash on the streets, which strikes westerners as so palpably and perceptibly awful when they step into developing countries, actually not be the most pressing issue facing the global south?